If you are familiar with our Embellished Manuscripts Collection, you have probably noticed by now that we have an infatuation with handwritten letters. Yet, beyond the historical relevance of correspondence or journal entries from famous artists and thinkers, we believe there’s something fascinating about the correspondence between everyday people from other times. There’s a beauty in those letters that ought to be shared. So, when we came across Christine Estima’s love letter collection we couldn’t wait to share it with you.

Christine is a freelance writer and storyteller from Toronto whose writing has appeared in many publications including The New York Times, The Globe and Mail, The Malahat Review and Room Magazine, among many others. She was also longlisted for the 2015 CBC Canada Writes Creative Non-fiction Prize and was a finalist in the 2011 Writers’ Union of Canada Short Prose Competition. She graciously granted us an interview to talk about her collection of over 200 love letters dating from World War I.

What was the inspiration behind starting your love letter collection?

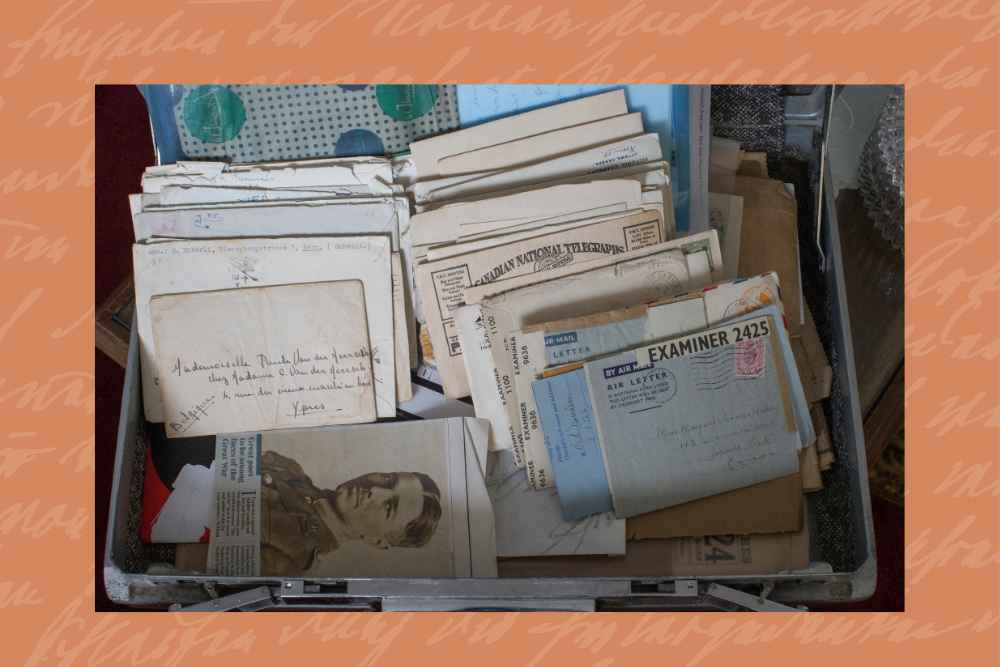

It began in 2013 when I had been living with a partner in Germany. After the relationship ended I found myself adrift; I wasn’t making a lot of money and I didn’t have a place to live anymore so I was just floating through Europe, sleeping on strangers’ couches and getting a house-sitting gig wherever I could. One of my first house-sitting gigs was in Brussels and I discovered a nearby flea market. I had nothing else to do so every day I’d just go to the flea market and dig through boxes for hours on end, and I discovered entire boxes full of old love letters, telegrams and regular correspondence amongst people. You could buy entire stacks of love letters for about 1 Euro!

I was in a really sad place in my life. When you go through a breakup your self-esteem takes a hit and mine certainly did. I was in a spot where I felt like maybe I didn’t deserve love, maybe I was unlovable. And then I’d find these entire stacks of love letters and I’d buy them instead of buying a cup of coffee because I felt like the letters were feeding me more. I’d go through them and read these beautiful protestations of admiration, adoration, respect, love and romance. A lot of them were written during wartime, WWI and WWII, and sometimes in the interwar period, and I have a whole stack from the Korean War. I think it was reading other people’s letters that gave me my self-esteem back. I don’t necessarily think that things happen for a reason, I don’t think anything is fated, but I do think that me going through this was going to lead me somewhere else.

I’m a huge nostalgia person – my apartment is loaded with antiques – so it wasn’t just the romance. I love being around things that are loaded with history, and I think reading the epic stories of separation and love between people who came before me was really inspiring.

I also think there is a lot of beautiful language that we don’t really use anymore. Communication is so disposable now, but back then letters could take weeks or sometimes months to arrive, so people would really use the most powerful language and expressions that they could. I just really love the idea of writing to someone not knowing when they are going to get it and so you kind of say, “If I never hear from you again, I need you to know how I feel” instead of “Hey babe, what’s up!” [she laughs].

How did the collection continue to grow?

I eventually left Brussels and ended up living all over Europe. I was still house-sitting and in every city I’d search for their flea market. I was living out of a backpack and didn’t have a lot of space to pack things I bought, so I’d shove the letters in my iPad case to protect them and keep them flat. And then when I came back to Canada, I bought another stack of letters at the Sunday antique flea market here in Toronto.

What other treasures have you found?

I found this incredible journal from a man living in Manhattan in the 1840s, and it’s wild what he is describing – first of all because some of the streets either no longer exist or have been renamed. He is living in a boarding house which we don’t really see much anymore. He has a really nosy landlady who wants to set him up with her daughter and he is a very private person. The journal is very short, so I don’t really have a good sense of who he is or what he’s doing, but his name is on it and using ancestry.com I was able to find out more, like who his family is, and track his descendants. I’ve done that a lot when I get a new letter or a stack of letters, and the writers really interest me.

Have you contacted any of the descendants?

I wrote about this a few years ago for The Globe and Mail. I bought a huge stack of love letters here in Toronto that belonged to a Royal Canadian Air Force pilot. He was stationed overseas during WWII and from 1942 to 1944 he wrote to the sweetheart he left behind in Toronto, but then the letters stopped in 1944. If there were more I don’t have them, and I was curious about what happened: Did they ever see each other again like he said? Did they get married after the war like he promised?

The great thing about the Toronto Public Library is that if you use a library computer you can access ancestry.com for free, so I did some digging. I went through census records and voter rolls, and I found his declassified military file. I got news clippings and saw telegrams sent to his family, and it turned out that his squadron went missing over enemy skies in 1944, and the bodies of members of his squadron washed up on the shores of occupied France, but his never did. I did more digging to find out what happened to his sweetheart, and I found out that after he died she did get married and had a family. I was able to contact one of her children and I interviewed him. He couldn’t really tell me very much about his mother’s love affair with this RCAF officer because she didn’t marry him, she married his father. I wasn’t surprised because what mother tells the secrets of her heart to her kids, you know? But what he did tell me was that every once in a while, when his parents were fighting, his mother would make some sort of comment like, “If Edward hadn’t died, I would have married him,” so he knew the name of the RCAF officer, he had been mentioned and I thought that was really interesting.

Have you always been fascinated by storytelling even before becoming a writer?

Yes, I think I decided to be a writer in utero! I think I came out saying “Somebody hand me a pen and paper, I’ve got stories to write!” [she laughs]. I’ve been writing stories ever since I was a little girl, and I still have short stories that I used to bind myself, from when I was 6 or 7 years old. I always wanted to be a storyteller. I think it could be due to my curious nature, or the fact that I just love the written word. It could be a combination of those things. I’m fascinated by love letters or any kind of old correspondence or journals and diaries. A huge part of it is that there are so many wonderful stories that are forgotten to time, and these people are not famous and there’s never going to be an entry with their names in the encyclopedia, and a part of me feels like their stories deserve to be told and they deserve to be remembered. The fact that I was able to buy these love letters at the flea market is a little bit sad because nobody in their family thought that they were worth having. I feel like someone took a lot of care to write such beautiful letters, so someone ought to appreciate that.

Do you have a favourite letter from your collection?

That’s a difficult question because they are all like my babies! [she laughs].

There’s another great letter that I bought in Vienna. It’s just a single letter written in English, which caught my attention because any other letter that I found in Vienna was written in German. It’s dated 1946 so the war was just over and he is writing to a woman named Annie in the UK. The very first line of the letter is “I was just released from a Soviet POW camp,” which suggests to me that he was a soldier in the Third Reich, you know? And he writes, “You still remember me, don’t you? I’m sure you can imagine how much I want to hear from you.” At the end of the letter there is a PS that reads, “If this isn’t Annie’s address, can you please forward it on to her?” The reason I was able to buy it in Vienna is because the envelope has “Return to sender” on it. It’s a very short letter, and it’s typewritten – which is also a godsend because some of the handwritten ones are so hard to read! But there are a lot of things about the letter that I thought required further investigation because 1) he was in a Soviet POW camp, which means he was a Nazi soldier, and 2) he’s writing to a woman whose last name is Reichman, which sounds very German but also Jewish. So, he was a Nazi soldier in love with a Jewish woman before the war. One of the important aspects of the letter is that he writes, “I haven’t seen you in eight years.” So, 1946 minus eight is right before the war. Also, he is sending her a letter written in English to England, so was he in love with an English woman before the war?

I did a whole bunch of digging for this one: I went back to Vienna several times, I went to the Jewish archives, I went through the military records, I visited graves, I found the names of descendants, I have a huge stack of city archives. I was able to find out a lot but some of my questions still haven’t been answered. What I was able to determine was that yes, Annie was Jewish, but she wasn’t English. She was from Vienna and before the war (because Austria was annexed before the war started) her father was in prison that had a concentration camp after the annexation of Austria. And her family paid every last penny they had to basically bribe him out and as soon as they did, they fled through the UK. So, I think that’s the last known address the soldier had. I was able to find out that she settled in New York and had a family, she worked in publishing and she lived a long life. For him, he actually received the Iron Cross Second Class from the Nazis – the equivalent of a corporal – and was very important within the Nazi army. But I still haven’t been able to find out, how were they friends? Were they lovers? What happened between them before the war? I held off contacting their descendants on that one because it’s such a sensitive topic.

It’s very brief, that letter, but it has inspired a world of curiosity and fascination, so it’s probably one of my favourites.

Are these stories finding their way into your writing or your work?

I’ve written the manuscript of a novel that’s not published yet, but it does have an epistolary aspect to it for sure. It’s about Kafka and the greatest love of his life, Milena Jesenská. They wrote love letters to each other and his letters to her were famously published after his death in a book called Letters to Milena, but her letters to him didn’t survive. We don’t know what happened to them, there’s no record of them. In my manuscript I imagined what her letters to him might have been, so I titled the book Letters to Kafka.

Are you still adding more letters to your collection?

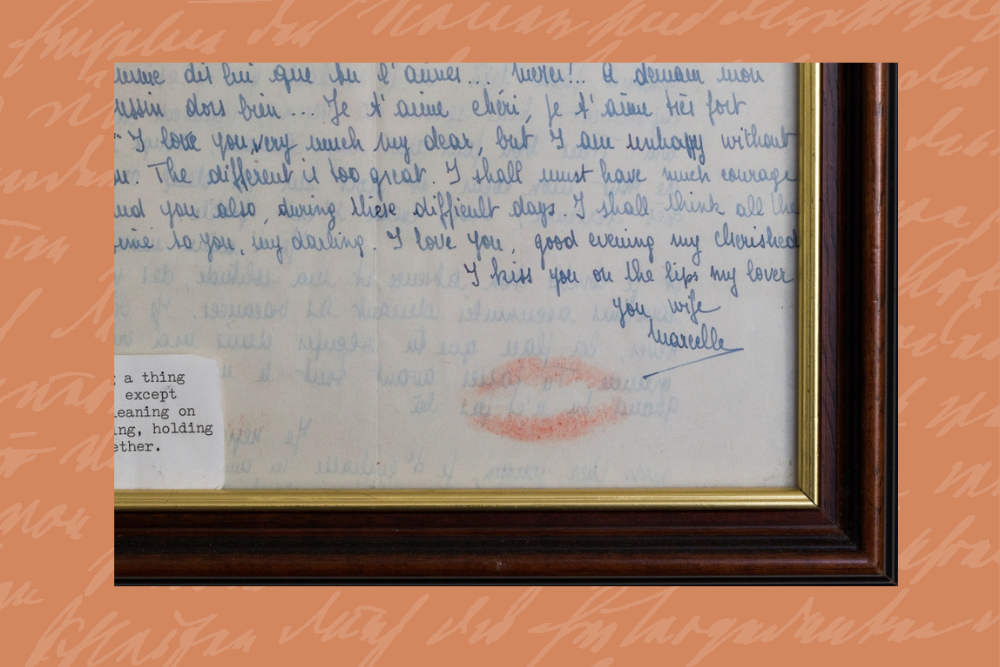

Yes! The pandemic kind of put a stop to it because the flea markets shut down, but they are starting up again. I recently bought a stack at the flea market here. It’s a Toronto couple from the 1920s and there is no major drama in their correspondence – he’s a travelling salesman, he’s in love with her, they make plans to marry once he comes back from his travels all around Ontario. What’s most interesting about it, though, is reading aspects of Toronto the way it was a hundred years ago. For example, he’s writing about the cost of things and talking about places in Toronto that either don’t exist anymore or they still do, but they are a little bit different. He’s also writing about his business and the items he is selling, and these are things that we don’t have anymore or have no need for, like replacement parts for medical instruments that no longer exist. I’m a big history person and I just love being able to transport back in time to this era. There’s also something really visceral about this because you are literally holding the letter that was written a hundred years ago, and you can see the penmanship and things like an ink smudge here or an inkblot or watermark. I have one letter on my wall that has a lipstick kiss on it. So, it’s very tactile and it really is a form of time travel because it’s not like you are in a museum – it’s on a wall framed, you are holding it and touching it, so it’s very much a way to be connected.

Thank you, Christine, for sharing your amazing story with us.

To read more about Christine, please visit her website.

Wonderful post!